File System¶

In this chapter, you will learn how to work with file systems.

Objectives: In this chapter, future Linux administrators will learn how to:

manage partitions on disk;

use LVM for a better use of disk resources;

provide users with a filesystem and manage the access rights.

and also discover:

how the tree structure is organized in Linux;

the different types of files offered and how to work with them;

hardware, disk, partition, lvm, linux

Knowledge:

Complexity:

Reading time: 20 minutes

Partitioning¶

Partitioning will allow the installation of several operating systems because it is impossible for them to cohabit on the same logical drive. It also allows the separation of data logically (security, access optimization, etc.).

The partition table, stored in the first sector of the disk (MBR: Master Boot Record), records the division of the physical disk into partitioned volumes.

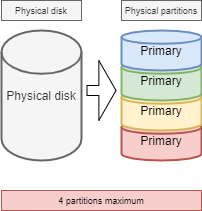

For MBR partition table types, the same physical disk can be divided into a maximum of 4 partitions:

- Primary partition (or main partition)

- Extended partition

Warning

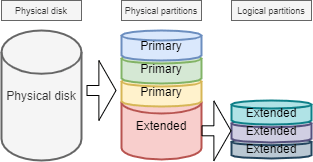

There can be only one extended partition per physical disk. That is, a physical disk can have in the MBR partition table up to:

- Three primary partitions plus one extended partition

- Four primary partitions

The extended partition cannot write data and format and can only contain logical partitions. The largest physical disk that the MBR partition table can recognize is 2TB.

Naming conventions for device file names¶

In the world of GNU/Linux, everything is a file. For disks, they are recognized in the system as:

| Hardware | Device file name |

|---|---|

| IDE hard disk | /dev/hd[a-d] |

| SCSI/SATA/USB hard disk | /dev/sd[a-z] |

| Optical drive | /dev/cdrom or /dev/sr0 |

| Floppy disk | /dev/fd[0-7] |

| Printer (25 pins) | /dev/lp[0-2...] |

| Printer (USB) | /dev/usb/lp[0-15] |

| Mouse | /dev/mouse |

| Virtual hard disk | /dev/vd[a-z] |

The Linux kernel contains drivers for most hardware devices.

What we call devices are the files stored without /dev, identifying the different hardware detected by the motherboard.

The service called udev is responsible for applying the naming conventions (rules) and applying them to the devices it detects.

For more information, please see here.

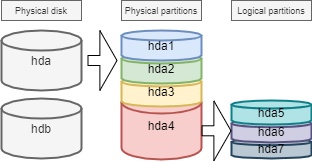

Device partition number¶

The number after the block device (storage device) indicates a partition. For MBR partition tables, the number 5 must be the first logical partition.

Warning

Attention please! The partition number we mentioned here mainly refers to the partition number of the block device (storage device).

There are at least two commands for partitioning a disk: fdisk and cfdisk. Both commands have an interactive menu. cfdisk is more reliable and better optimized, so it is best to use it.

The only reason to use fdisk is when you want to list all logical devices with the -l option. fdisk uses MBR partition tables, so it is not supported for GPT partition tables and cannot be processed for disks larger than 2TB.

sudo fdisk -l

sudo fdisk -l /dev/sdc

sudo fdisk -l /dev/sdc2

parted command¶

The parted (partition editor) command can partition a disk without the drawbacks of fdisk.

The parted command can be used on the command line or interactively. It also has a recovery function capable of rewriting a deleted partition table.

parted [-l] [device]

Under the graphical interface, there is the very complete gparted tool: Gnome PARtition EDitor.

The gparted -l command lists all logical devices on a computer.

The gparted command, when run without any arguments, will show an interactive mode with its internal options:

helpor an incorrect command will display these options.print allin this mode will have the same result asgparted -lon the command line.quitto return to the prompt.

cfdisk command¶

The cfdisk command is used to manage partitions.

cfdisk device

Example:

$ sudo cfdisk /dev/sda

Disk: /dev/sda

Size: 16 GiB, 17179869184 bytes, 33554432 sectors

Label: dos, identifier: 0xcf173747

Device Boot Start End Sectors Size Id Type

>> /dev/sda1 * 2048 2099199 2097152 1G 83 Linux

/dev/sda2 2099200 33554431 31455232 15G 8e Linux LVM

lqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqk

x Partition type: Linux (83) x

x Attributes: 80 x

xFilesystem UUID: 54a1f5a7-b8fa-4747-a87c-2dd635914d60 x

x Filesystem: xfs x

x Mountpoint: /boot (mounted) x

mqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqqj

[Bootable] [ Delete ] [ Resize ] [ Quit ] [ Type ] [ Help ]

[ Write ] [ Dump ]

The preparation, without LVM, of the physical media goes through five steps:

- Setting up the physical disk;

- Partitioning of the volumes (a division of the disk, possibility of installing several systems, ...);

- Creation of the file systems (allows the operating system to manage the files, the tree structure, the rights, ...);

- Mounting of file systems (registration of the file system in the tree structure);

- Manage user access.

Logical Volume Manager (LVM)¶

Logical Volume Manager (LVM)

The partition created by the standard partition cannot dynamically adjust the resources of the hard disk, once the partition is mounted, the capacity is completely fixed, this constraint is unacceptable on the server. Although the standard partition can be forcibly expanded or shrunk through certain technical means, it can easily cause data loss. LVM can solve this problem very well. LVM is available under Linux from kernel version 2.4, and its main features are:

- More flexible disk capacity;

- Online data movement;

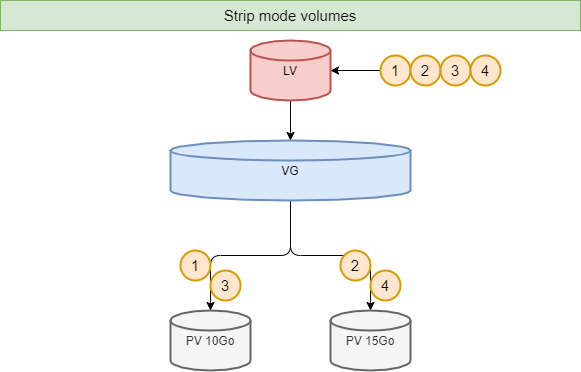

- Disks in stripe mode;

- Mirrored volumes (recopy);

- Volume snapshots (snapshot).

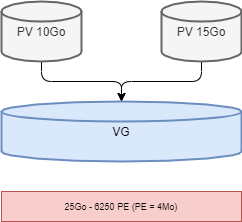

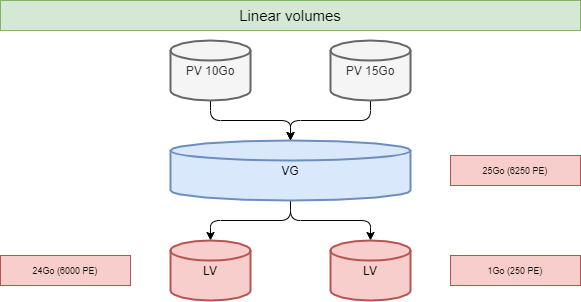

The principle of LVM is very simple:

- a logical abstraction layer is added between the physical disk (or disk partition) and the file system

- merge multiple disks (or disk partition) into Volume Group(VG)

- perform underlying disk management operations on them through something called Logical Volume(LV).

The physical media: The storage medium of the LVM can be the entire hard disk, disk partition, or RAID array. The device must be converted, or initialized, to an LVM Physical Volume(PV), before further operations can be performed.

PV(Physical Volume) is the basic storage logic block of LVM. You can create a physical volume by using a disk partition or the disk itself.

VG(Volume Group): Similar to physical disks in a standard partition, a VG consists of one or more PV.

LV(Logical Volume): Similar to hard disk partitions in standard partitions, LV is built on top of VG. You can set up a file system on LV.

PE: The smallest unit of storage that can be allocated in a Physical Volume, default to 4MB. You can specify an additional size.

LE: The smallest unit of storage that can be allocated in a Logical Volume. In the same VG, PE, and LE are the same and correspond one to one.

The disadvantage is that if one of the physical volumes becomes out of order, then all the logical volumes that use this physical volume are lost. You will have to use LVM on raid disks.

Note

LVM is only managed by the operating system. Therefore the BIOS needs at least one partition without LVM to boot.

Info

In the physical disk, the smallest storage unit is the sector, in the file system, the smallest storage unit of GNU/Linux is the block, which is called cluster in the Windows operating system. In RAID, the smallest storage unit is chunk.

The Writing Mechanism of LVM¶

There are several storage mechanisms when storing data to LV, two of which are:

- Linear volumes;

- Volumes in stripe mode;

- Mirrored volumes.

LVM commands for volume management¶

The main relevant commands are as follows:

| Item | PV | VG | LV |

|---|---|---|---|

| scan | pvscan | vgscan | lvscan |

| create | pvcreate | vgcreate | lvcreate |

| display | pvdisplay | vgdisplay | lvdisplay |

| remove | pvremove | vgremove | lvremove |

| extend | vgextend | lvextend | |

| reduce | vgreduce | lvreduce | |

| summary information | pvs | vgs | lvs |

pvcreate command¶

The pvcreate command is used to create physical volumes. It turns Linux partitions (or disks) into physical volumes.

pvcreate [-options] partition

Example:

[root]# pvcreate /dev/hdb1

pvcreate -- physical volume « /dev/hdb1 » successfully created

You can also use a whole disk (which facilitates disk size increases in virtual environments for example).

[root]# pvcreate /dev/hdb

pvcreate -- physical volume « /dev/hdb » successfully created

# It can also be written in other ways, such as

[root]# pvcreate /dev/sd{b,c,d}1

[root]# pvcreate /dev/sd[b-d]1

| Option | Description |

|---|---|

-f |

Forces the creation of the volume (disk already transformed into physical volume). Use with extreme caution. |

vgcreate command¶

The vgcreate command creates volume groups. It groups one or more physical volumes into a volume group.

vgcreate <VG_name> <PV_name...> [option]

Example:

[root]# vgcreate volume1 /dev/hdb1

…

vgcreate – volume group « volume1 » successfully created and activated

[root]# vgcreate vg01 /dev/sd{b,c,d}1

[root]# vgcreate vg02 /dev/sd[b-d]1

lvcreate command¶

The lvcreate command creates logical volumes. The file system is then created on these logical volumes.

lvcreate -L size [-n name] VG_name

Example:

[root]# lvcreate –L 600M –n VolLog1 volume1

lvcreate -- logical volume « /dev/volume1/VolLog1 » successfully created

| Option | Description |

|---|---|

-L size |

Sets the logical volume size in K, M, or G. |

-n name |

Sets the LV name. A special file was created in /dev/name_volume with this name. |

-l number |

Sets the percentage of the capacity of the hard disk to use. You can also use the number of PE. One PE equals 4MB. |

Info

After you create a logical volume with the lvcreate command, the naming rule of the operating system is - /dev/VG_name/LV_name, this file type is a soft link (otherwise known as a symbolic link). The link file points to files like /dev/dm-0 and /dev/dm-1.

LVM commands to view volume information¶

pvdisplay command¶

The pvdisplay command allows you to view information about the physical volumes.

pvdisplay /dev/PV_name

Example:

[root]# pvdisplay /dev/PV_name

vgdisplay command¶

The vgdisplay command allows you to view information about volume groups.

vgdisplay VG_name

Example:

[root]# vgdisplay volume1

lvdisplay command¶

The lvdisplay command allows you to view information about the logical volumes.

lvdisplay /dev/VG_name/LV_name

Example:

[root]# lvdisplay /dev/volume1/VolLog1

Preparation of the physical media¶

The preparation with LVM of the physical support is broken down into the following:

- Setting up the physical disk

- Partitioning of the volumes

- LVM physical volume

- LVM volume groups

- LVM logical volumes

- Creating file systems

- Mounting file systems

- Manage user access

Structure of a file system¶

A file system FS is in charge of the following actions:

- Securing access and modification rights to files;

- Manipulating files: create, read, modify, and delete;

- Locating files on the disk;

- Managing partition space.

The Linux operating system is able to use different file systems (ext2, ext3, ext4, FAT16, FAT32, NTFS, HFS, BtrFS, JFS, XFS, ...).

mkfs command¶

The mkfs(make file system) command allows you to create a Linux file system.

mkfs [-t fstype] filesys

Example:

[root]# mkfs -t ext4 /dev/sda1

| Option | Description |

|---|---|

-t |

Indicates the type of file system to use. |

Warning

Without a file system it is not possible to use the disk space.

Each file system has an identical structure on each partition. The system initializes a Boot Sector and a Super block, and then the administrator initializes an Inode table and a Data block.

Note

The only exception is the swap partition.

Boot sector¶

The boot sector is the first sector of bootable storage media, that is, 0 cylinder, 0 track, 1 sector(1 sector equals 512 bytes). It consists of three parts:

- MBR(master boot record): 446 bytes.

- DPT(disk partition table): 64 bytes.

- BRID(boot record ID): 2 bytes.

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| MBR | Stores the "boot loader"(or "GRUB"); loads the kernel, passes parameters; provides a menu interface at boot time; transfers to another loader, such as when multiple operating systems are installed. |

| DPT | Records the partition status of the entire disk. |

| BRID | Determines whether the device is usable to boot. |

Super block¶

The size of the Super block table is defined at creation. It is present on each partition and contains the elements necessary for its utilization.

It describes the File System:

- Name of the Logical Volume;

- Name of the File System;

- Type of the File System;

- File System Status;

- Size of the File System;

- Number of free blocks;

- Pointer to the beginning of the list of free blocks;

- Size of the inode list;

- Number and list of free inodes.

After the system is initialized, a copy is loaded into the central memory. This copy is updated as soon as modified, and the system saves it periodically (command sync).

When the system stops, it copies this table in memory to its block.

Table of inodes¶

The size of the inode table is defined at its creation and is stored on the partition. It consists of records, called inodes, corresponding to the files created. Each record contains the addresses of the data blocks making up the file.

Note

An inode number is unique within a file system.

After the system is initialized, a copy is loaded into the central memory. This copy is updated as soon as it is modified, and the system saves it periodically (command sync).

When the system stops, it copies this table in memory to its block.

A file is managed by its inode number.

Note

The size of the inode table determines the maximum number of files the FS can contain.

Information present in the inode table :

- Inode number;

- File type and access permissions;

- Owner identification number;

- Identification number of the owner group;

- Number of links on this file;

- Size of the file in bytes;

- Date the file was last accessed;

- Date the file was last modified;

- Date of the last modification of the inode (= creation);

- Table of several pointers (block table) to the logical blocks containing the file pieces.

Data block¶

Its size corresponds to the rest of the partition's available space. This area contains the catalogs corresponding to each directory and the data blocks corresponding to the file's contents.

To guarantee the consistency of the file system, an image of the superblock and the inode table is loaded into memory (RAM) when the operating system is loaded so that all I/O operations are done through these system tables. When the user creates or modifies files, this memory image is updated first. The operating system must, therefore, regularly update the superblock of the logical disk (sync command).

These tables are written to the hard disk when the system is shut down.

Attention

In the event of a sudden stop, the file system may lose its consistency and cause data loss.

Repairing the file system¶

It is possible to check the consistency of a file system with the fsck command.

In case of errors, solutions are proposed to repair the inconsistencies. After repair, files that remain without entries in the inode table are attached to the logical drive's /lost+found folder.

fsck command¶

The fsck command is a console-mode integrity check and repair tool for Linux file systems.

fsck [-sACVRTNP] [ -t fstype ] filesys

Example:

[root]# fsck /dev/sda1

To check the root partition, it is possible to create a forcefsck file and reboot or run shutdown with the -F option.

[root]# touch /forcefsck

[root]# reboot

or

[root]# shutdown –r -F now

Warning

The partition to be checked must be unmounted.

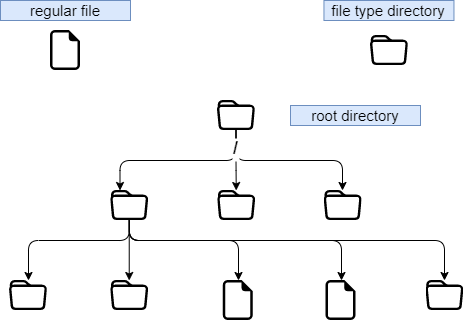

Organization of a file system¶

By definition, a File System is a tree structure of directories built from a root directory (a logical device can only contain one file system).

Note

In Linux, everything is a file.

Text document, directory, binary, partition, network resource, screen, keyboard, Unix kernel, user program, ...

Linux meets the FHS (Filesystems Hierarchy Standard) (see man hier), which defines the folders' names and roles.

| Directory | Functionality | Complete word |

|---|---|---|

/ |

Contains special directories | |

/boot |

Files related to system startup | |

/sbin |

Commands necessary for system startup and repair | system binaries |

/bin |

Executables of basic system commands | binaries |

/usr/bin |

System administration commands | |

/lib |

Shared libraries and kernel modules | libraries |

/usr |

Saves data resources related to UNIX | UNIX System Resources |

/mnt |

Temporary mount point directory | mount |

/media |

For mounting removable media | |

/misc |

To mount the shared directory of the NFS service. | |

/root |

Administrator's login directory | |

/home |

The upper-level directory of a common user's home directory | |

/tmp |

The directory containing temporary files | temporary |

/dev |

Special device files | device |

/etc |

Configuration and script files | editable text configuration |

/opt |

Specific to installed applications | optional |

/proc |

This is a mount point for the proc filesystem, which provides information about running processes and the kernel | processes |

/var |

This directory contains files which may change in size, such as spool and log files | variables |

/sys |

Virtual file system, similar to /proc | |

/run |

That is /var/run | |

/srv |

Service Data Directory | service |

- To mount or unmount at the tree level, you must not be under its mount point.

- Mounting on a non-empty directory does not delete the content. It is only hidden.

- Only the administrator can perform mounts.

- Mount points automatically mounted at boot time must be entered in

/etc/fstab.

/etc/fstab file¶

The /etc/fstab file is read at system startup and contains the mounts to be performed. Each file system to be mounted is described on a single line, the fields being separated by spaces or tabs.

Note

Lines are read sequentially (fsck, mount, umount).

/dev/mapper/VolGroup-lv_root / ext4 defaults 1 1

UUID=46….92 /boot ext4 defaults 1 2

/dev/mapper/VolGroup-lv_swap swap swap defaults 0 0

tmpfs /dev/shm tmpfs defaults 0 0

devpts /dev/pts devpts gid=5,mode=620 0 0

sysfs /sys sysfs defaults 0 0

proc /proc proc defaults 0 0

1 2 3 4 5 6

| Column | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | File system device (/dev/sda1, UUID=..., ...) |

| 2 | Mount point name, absolute path (except swap) |

| 3 | Filesystem type (ext4, swap, ...) |

| 4 | Special options for mounting (defaults, ro, ...) |

| 5 | Enable or disable backup management (0:not backed up, 1:backed up). The dump command is used for backup here. This outdated feature was initially designed to back up old file systems on tape. |

| 6 | Check order when checking the FS with the fsck command (0:no check, 1:priority, 2:not priority) |

The mount -a command allows you to mount automatically based on the contents of the configuration file /etc/fstab. The mounted information is then written to /etc/mtab.

Warning

Only the mount points listed in /etc/fstab will be mounted on reboot. Generally speaking, we do not recommend writing USB flash disks and removable hard drives to the /etc/fstab file because when the external device is unplugged and rebooted, the system will prompt that the device cannot be found, resulting in a failure to boot. So what am I supposed to do? Temporary mount, for example:

Shell > mkdir /mnt/usb

Shell > mount -t vfat /dev/sdb1 /mnt/usb

# Read the information of the USB flash disk

Shell > cd /mnt/usb/

# When not needed, execute the following command to pull out the USB flash disk

Shell > umount /mnt/usb

Info

It is possible to make a copy of the /etc/mtab file or to copy its contents to /etc/fstab.

If you want to view the UUID of the device partition number, type the following command: lsblk -o name,uuid. UUID is the abbreviation of Universally Unique Identifier.

Mount management commands¶

mount command¶

The mount command allows you to mount and view the logical drives in the tree.

mount [-option] [device] [directory]

Example:

[root]# mount /dev/sda7 /home

| Option | Description |

|---|---|

-n |

Sets mount without writing to /etc/mtab. |

-t |

Indicates the type of file system to use. |

-a |

Mounts all filesystems mentioned in /etc/fstab. |

-r |

Mounts the file system read-only (equivalent to -o ro). |

-w |

Mounts the file system read/write, by default (equivalent -o rw). |

-o opts |

The opts argument is a comma-separated list (remount, ro, ...). |

Note

The mount command alone displays all mounted file systems. If the mount parameter is -o defaults, it is equivalent to -o rw,suid,dev,exec,auto,nouser,async and these parameters are independent of the file system. If you need to browse special mount options related to the file system, please read the "Mount options FS-TYPE" section in man 8 mount (FS-TYPE is replaced with the corresponding file system, such as ntfs, vfat, ufs, etc.)

umount command¶

The umount command is used to unmount logical drives.

umount [-option] [device] [directory]

Example:

[root]# umount /home

[root]# umount /dev/sda7

| Option | Description |

|---|---|

-n |

Sets mounting removal without writing to /etc/mtab. |

-r |

Remounts as read-only if umount fails. |

-f |

Forces mounting removal. |

-a |

Removes mounts of all filesystems mentioned in /etc/fstab. |

Note

When disassembling, you must not stay below the mounting point. Otherwise, the following error message is displayed: device is busy.

File naming convention¶

As in any system, it is important to respect the file naming rules to navigate the tree structure and file management.

- Files are coded on 255 characters;

- All ASCII characters can be used;

- Uppercase and lowercase letters are differentiated;

- Most files do not have a concept for file extension. In the GNU/Linux world, most file extensions are not required, except for a few (for example, .jpg, .mp4, .gif, etc.).

Groups of words separated by spaces must be enclosed in quotation marks:

[root]# mkdir "working dir"

Note

While nothing is technically wrong with creating a file or directory with a space, it is generally a "best practice" to avoid this and replace any space with an underscore.

Note

The . at the beginning of the file name only hides it from a simple ls.

Examples of file extension agreements:

.c: source file in C language;.h: C and Fortran header file;.o: object file in C language;.tar: data file archived with thetarutility;.cpio: data file archived with thecpioutility;.gz: data file compressed with thegziputility;.tgz: data file archived with thetarutility and compressed with thegziputility;.html: web page.

Details of a file name¶

[root]# ls -liah /usr/bin/passwd

266037 -rwsr-xr-x 1 root root 59K mars 22 2019 /usr/bin/passwd

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

| Part | Description |

|---|---|

1 |

Inode number |

2 |

File type (1st character of the block of 10), "-" means this is an ordinary file. |

3 |

Access rights (last 9 characters of the block of 10) |

4 |

If this is a directory, this number represents how many subdirectories there are in that directory, including hidden ones. If this is a file, it indicates the number of hard links. When the number 1 is, there is only one hard link. |

5 |

Name of the owner |

6 |

Name of the group |

7 |

Size (byte, kilo, mega) |

8 |

Date of last update |

9 |

Name of the file |

In the GNU/Linux world, there are seven file types:

| File types | Description |

|---|---|

| - | Represents an ordinary file. Including plain text files (ASCII); binary files (binary); data format files (data); various compressed files. |

| d | Represents a directory file. |

| b | Represents a block device file. It includes hard drives, USB drives, and so on. |

| c | Represents a character device file. Interface device of serial port, such as mouse, keyboard, etc. |

| s | Represents a socket file. It is a file specially used for network communication. |

| p | Represents a pipe file. It is a special file type. The main purpose is to solve the errors caused by multiple programs accessing a file simultaneously. FIFO is the abbreviation of first-in-first-out. |

| l | Represents soft link files, also called symbolic link files, are similar to shortcuts in Windows. Hard link file, also known as physical link file. |

Supplementary description of the directory¶

Each directory has two hidden files: . and ... You need to use ls -al to view, for example:

# . Indicates that in the current directory, for example, you need to execute a script in a directory, usually:

Shell > ./scripts

# .. represents the directory one level above the current directory, for example:

Shell > cd /etc/

Shell > cd ..

Shell > pwd

/

# For an empty directory, its fourth part must be greater than or equal to 2. Because there are "." and ".."

Shell > mkdir /tmp/t1

Shell > ls -ldi /tmp/t1

1179657 drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Nov 14 18:41 /tmp/t1

Special files¶

To communicate with peripherals (hard disks, printers, etc.), Linux uses interface files called special files (device file or special file). These files allow the peripherals to identify themselves.

These files are special because they do not contain data but specify the access mode to communicate with the device.

They are defined in two modes:

- block mode;

- character mode.

# Block device file

Shell > ls -l /dev/sda

brw------- 1 root root 8, 0 jan 1 1970 /dev/sda

# Character device file

Shell > ls -l /dev/tty0

crw------- 1 root root 8, 0 jan 1 1970 /dev/tty0

Communication files¶

These are the pipe (pipes) and the socket files.

-

Pipe files pass information between processes by FIFO (First In, First Out). One process writes transient information to a pipe file, and another reads it. After reading, the information is no longer accessible.

-

Socket files allow bidirectional inter-process communication (on local or remote systems). They use an inode of the file system.

Link files¶

These files allow the possibility of giving several logical names to the same physical file. A new access point to the file is therefore created.

There are two types of link files:

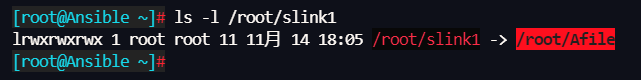

- Soft link files, also called symbolic link files;

- Hard link files, also called physical link files.

Their main features are:

| Link types | Description |

|---|---|

| soft link file | Represents a shortcut similar to Windows. It has permission of 777 and points to the original file. When the original file is deleted, the linked file and the original file are displayed in red. |

| Hard link file | Represents the original file. It has the same _ inode_ number as the hard-linked file. They can be updated synchronously, including the contents of the file and when it was modified. Cannot cross partitions, cannot cross file systems. Cannot be used for directories. |

Specific examples are as follows:

# Permissions and the original file to which they point

Shell > ls -l /etc/rc.locol

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 13 Oct 25 15:41 /etc/rc.local -> rc.d/rc.local

# When deleting the original file. "-s" represents the soft link option

Shell > touch /root/Afile

Shell > ln -s /root/Afile /root/slink1

Shell > rm -rf /root/Afile

Shell > cd /home/paul/

Shell > ls –li letter

666 –rwxr--r-- 1 root root … letter

# The ln command does not add any options, indicating a hard link

Shell > ln /home/paul/letter /home/jack/read

# The essence of hard links is the file mapping of the same inode number in different directories.

Shell > ls –li /home/*/*

666 –rwxr--r-- 2 root root … letter

666 –rwxr--r-- 2 root root … read

# If you use a hard link to a directory, you will be prompted:

Shell > ln /etc/ /root/etc_hardlink

ln: /etc: hard link not allowed for directory

File attributes¶

Linux is a multi-user operating system where the control of access to files is essential.

These controls are functions of:

- file access permissions ;

- users (ugo Users Groups Others).

Basic permissions of files and directories¶

The description of file permissions is as follows:

| File permissions | Description |

|---|---|

| r | Read. Allows reading a file (cat, less, ...) and copying a file (cp, ...). |

| w | Write. Allows modification of the file content (cat, >>, vim, ...). |

| x | Execute. Considers the file as an eXecutable (binary or script). |

| - | No right |

The description of directory permissions is as follows:

| Directory permissions | Description |

|---|---|

| r | Read. Allows reading the contents of a directory (ls -R). |

| w | Write. Allows you to create, and delete files/directories in this directory, such as commands mkdir, rmdir, rm, touch, and so on. |

| x | Execute. Allows descending in the directory (cd). |

| - | No right |

Info

For a directory's permissions, r and x usually appear at the same time. Moving or renaming a file depends on whether the directory where it is located has w permission, and so does deleting a file.

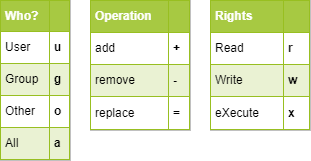

User type corresponding to basic permission¶

| User type | Description |

|---|---|

| u | Owner |

| g | Owner group |

| o | Others users |

Info

In some commands, it is possible to designate everyone with a (all). a = ugo.

Attribute management¶

The display of rights is done with the command ls -l. It is the last 9 characters of the block of 10. More precisely 3 times 3 characters.

[root]# ls -l /tmp/myfile

-rwxrw-r-x 1 root sys ... /tmp/myfile

1 2 3 4 5

| Part | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Owner (user) permissions, here rwx |

| 2 | Owner group permissions (group), here rw- |

| 3 | Other users' permissions (others), here r-x |

| 4 | File owner |

| 5 | Group owner of the file |

By default, the owner of a file is the one who created it. The group of the file is the group of the owner who created the file. The others are those not concerned by the previous cases.

The attributes are changed with the chmod command.

Only the administrator and the owner of a file can change the rights of a file.

chmod command¶

The chmod command allows you to change the access permissions to a file.

chmod [option] mode file

| Option | Observation |

|---|---|

-R |

Recursively change the permissions of the directory and all files under the directory. |

Warning

The rights of files and directories are not dissociated. For some operations, it will be necessary to know the rights of the directory containing the file. A write-protected file can be deleted by another user as long as the rights of the directory containing it allow this user to perform this operation.

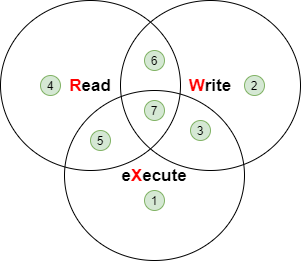

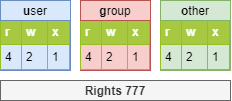

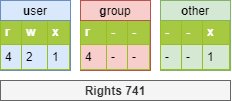

The mode indication can be an octal representation (e.g. 744) or a symbolic representation ([ugoa][+=-][rwxst]).

Octal (or number)representation:¶

| Number | Description |

|---|---|

| 4 | r |

| 2 | w |

| 1 | x |

| 0 | - |

Add the three numbers together to get one user type permission. E.g. 755=rwxr-xr-x.

Info

Sometimes you will see chmod 4755. The number 4 here refers to the special permission set uid. Special permissions will not be expanded here for the moment, just as a basic understanding.

[root]# ls -l /tmp/fil*

-rwxrwx--- 1 root root … /tmp/file1

-rwx--x--- 1 root root … /tmp/file2

-rwx--xr-- 1 root root … /tmp/file3

[root]# chmod 741 /tmp/file1

[root]# chmod -R 744 /tmp/file2

[root]# ls -l /tmp/fic*

-rwxr----x 1 root root … /tmp/file1

-rwxr--r-- 1 root root … /tmp/file2

symbolic representation¶

This method can be considered as a "literal" association between a user type, an operator, and rights.

[root]# chmod -R u+rwx,g+wx,o-r /tmp/file1

[root]# chmod g=x,o-r /tmp/file2

[root]# chmod -R o=r /tmp/file3

Default rights and mask¶

When a file or directory is created, it already has permissions.

- For a directory:

rwxr-xr-xor 755. - For a file:

rw-r-r-or 644.

This behavior is defined by the default mask.

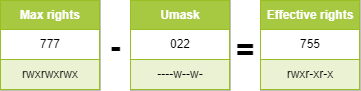

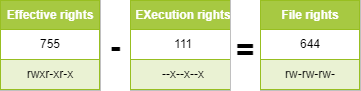

The principle is to remove the value defined by the mask at maximum rights without the execution right.

For a directory:

For a file, the execution rights are removed:

Info

The /etc/login.defs file defines the default UMASK, with a value of 022. This means the permission to create a file is 755 (rwxr-xr-x). However, for the sake of security, GNU/Linux does not have x permission for newly created files. This restriction applies to root(uid=0) and ordinary users(uid>=1000).

# root user

Shell > touch a.txt

Shell > ll

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Oct 8 13:00 a.txt

umask command¶

The umask command allows you to display and modify the mask.

umask [option] [mode]

Example:

$ umask 033

$ umask

0033

$ umask -S

u=rwx,g=r,o=r

$ touch umask_033

$ ls -la umask_033

-rw-r--r-- 1 rockstar rockstar 0 nov. 4 16:44 umask_033

$ umask 025

$ umask -S

u=rwx,g=rx,o=w

$ touch umask_025

$ ls -la umask_025

-rw-r---w- 1 rockstar rockstar 0 nov. 4 16:44 umask_025

| Option | Description |

|---|---|

-S |

Symbolic display of file rights. |

Warning

umask does not affect existing files. umask -S displays the file rights (without the execute right) of the files that will be created. So, it is not the display of the mask used to subtract the maximum value.

Note

umask modifies the mask until the disconnection.

Info

The umask command belongs to bash's built-in commands, so when you use man umask, all built-in commands will be displayed. If you only want to view the help of umask, you must use the help umask command.

To keep the value, you have to modify the following profile files:

For all users:

/etc/profile/etc/bashrc

For a particular user:

~/.bashrc

When the above file is written, it actually overrides the UMASK parameter of /etc/login.defs. If you want to improve the security of the operating system, you can set umask to 027 or 077.

Author: Antoine Morvan

Contributors: Steven Spencer, tianci li, Serge, Ganna Zhyrnova